Diet

You May Be on a Paleo Diet, but Is Your Microbiome?

How a meat–centric diet can starve your gut bacteria

Posted June 22, 2015

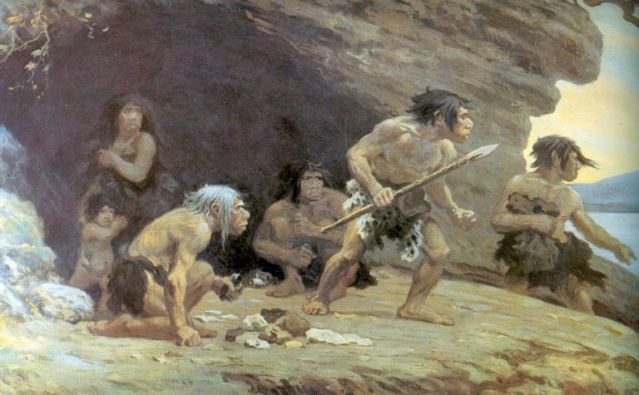

What is your mental image of a caveman? For many of us, our ancient ancestors were big, fearless brutes that hunted large game on the African savannah by day and roasted their fresh kill over the fire by night. The cavewomen might gather wild plants to supplement the zebra or impala dinner with handfuls of berries and maybe a couple tubers they unearthed. This scenario is what many of us envision when thinking about diet in the Paleolithic era, a time period that began about two and a half million years ago and ended 10,000 years ago when humans invented farming.

The modern day Paleolithic or paleo diet is based on the idea that our human genome can only evolve so fast (on the order of hundreds to thousands of years), but our diet and lifestyle in the modern world have changed in an evolutionary blink of an eye. This timescale mismatch sets up the possibility that our body has not had time to adapt to modern farmed and processed foods and because of this, our health is suffering. While this argument does make some intuitive sense, it assumes that we have a good understanding of what our ancestors ate.

The Hadza of Tanzania are the last remaining full-time hunter-gatherers in Africa. They are special because they practice a way of eating that humans espoused for greater than 99% of our time on the planet, and they live in the geographical cradle of human evolution, the Great Rift Valley. While these individuals are not living fossils of our ancient ancestors, they likely provide the best approximation of how our ancestors ate before the advent of farming, the domestication of livestock, and the proliferation of processed foods. The Hadza eat five main foods: wild tubers, berries, baobab seeds, and honey they gather, and meat from hunting. While the Hadza are more skilled with a bow and arrow than most of us, many days their hunting excursions are unsuccessful. On those days, the majority of their diet is tubers. These tubers are nothing like the sweet potatoes we have available in our local grocery stores. They are wild, fibrous roots that need to be chewed and chewed until a final ball of fiber they can’t swallow is spit out. Their heavy reliance on wild plants means the Hadza consume up to 150 grams of dietary fiber per day. Compare that to the average American, who eats about 15 grams.

The amount of fiber we consume is critical because these complex carbohydrates are what feed the approximately 100 trillion bacteria that live in our gut (our microbiota). These bacteria are holding the reins to our health. And based on recent studies of the microbiota from hunter-gatherers in Tanzania, Venezuela, Peru, and Papua New Guinea, it is clear that our Western microbiota leaves a lot to be desired. Some have said that hunter-gatherers should be renamed gatherer-hunters to more accurately reflect where the majority of their food comes from. Based on modern day hunter-gatherers, it is clear that the most of their diet is filled with high fiber plants, the food that feeds our gut bacteria.

Proponents of a paleo diet eschew whole grains and legumes reasoning that these products of agriculture are evolutionarily new and our bodies are not adapted to them. But if most meals contain a healthy portion of meat (as many paleo meals do) the question you need to ask yourself is whether you are eating enough fruits and vegetables to reach the FDA recommended amount of fiber (27-38 grams), never mind the 150 grams consumed by our Paleolithic ancestors. If not, you might be eating “paleo”, but your gut bacteria are not.

References:

1. Clemente, J.C., et al. “The microbiome of uncontacted Amerindians.” Sci. Adv. 1 (2015). Print.

2. Martinez, I., et al. “The gut microbiota of rural Papua New Guineans: composition, diversity patterns, and ecological processes.” Cell Reports. 11 (2015): 527. Print.

3. Obregon-Tito, A.J. et al. “Subsistence strategies in traditional societies distinguish gut microbiomes.” Nat. Commun. 6 (2015): 6505. Print.

4. Schnorr, S. L., et al. “Gut Microbiome of the Hadza Hunter-Gatherers.” Nat. Commun. 5 (2014): 3654. Print.

5. Sonnenburg, E.D. and Sonnenburg J.L. “Starving our microbial self: the deleterious consequences of a diet deficient in microbiota-accessible carbohydrates.” Cell. Metab. 5 (2014): 779. Print.